In the beta version of the tools, in order to change settings on a component, a settings widget needed to be built. This widget was written each time for each component. Even worse, it was impossible to do anything without a graphical user interface. You could not change a property on a component via command line, it had to be done through a UI. It. was. bad. You can see in the instantiation of the leg class, that it even took in the instance of the user interface! These two things should be totally separated and a component should never need to know about the user interface!

What the hell was I thinking?

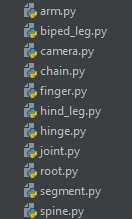

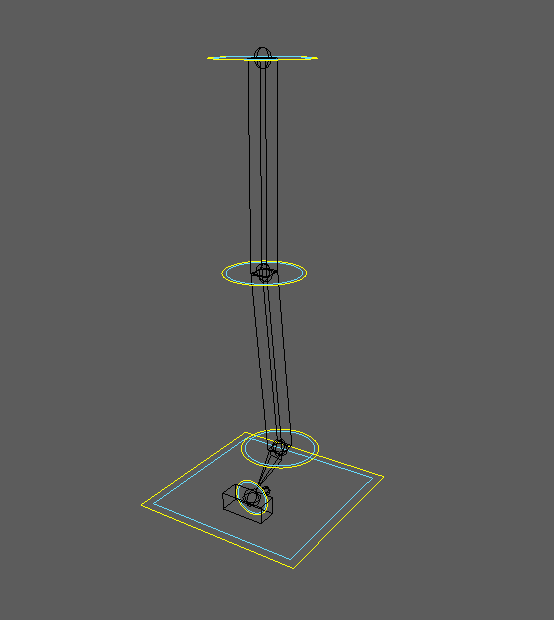

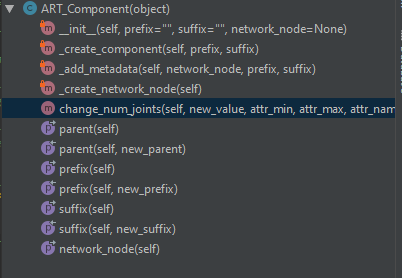

In order to address this, obviously things were rethought from the ground up. This is covered in previous posts, but to summarize, a component creates a network node. It uses properties to get and set data on the network node. The UI simply displays that data or calls on the setter for a property if a widget value is changed. You can see the general flow of this below.

Components are instantiated by either passing in no network node, in which case one is created, or if a network node is passed in, you create an instance with that data. You can see an example of that here:

Properties are an important element in this refactor. In order to have a component’s settings widget auto-generate, it simply gathers the properties of that class (including the inherited properties) and builds a widget off of those. By looking at the corresponding attribute types on the network node, it knows what type of widget to build. And because it’s a property, the changing of a widget value just calls on setattr! Here is what the code looks like for generating the property widgets and setting a property:

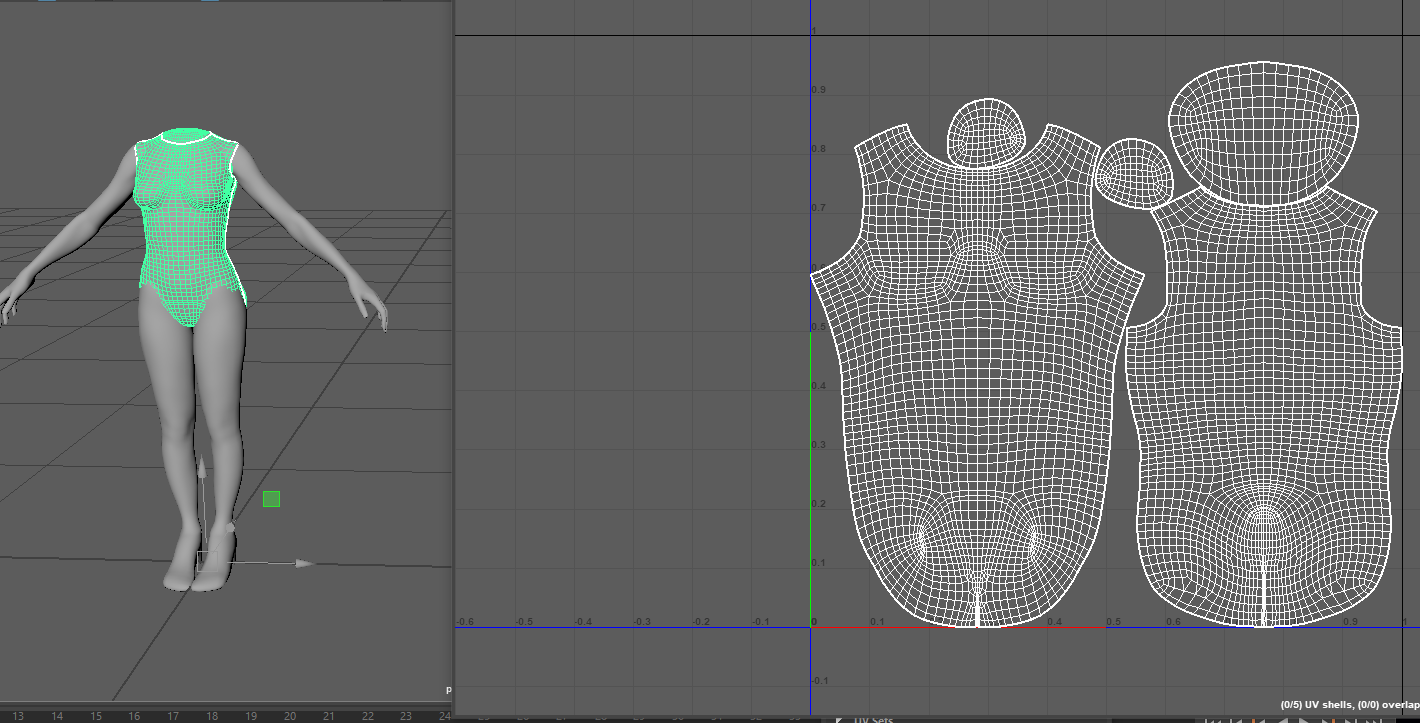

Okay, so let’s look at this in action. The UI has been redesigned to be faster and easier to use. In the clip below, when the Rig Builder is launched, it will create an asset and a root component. Then components can be added to the scene, which will add them to a list widget. Each item in the list widget has icons next to them for hiding that component in the scene, toggling aim mode, and toggling pin-in-place. Clicking on an item builds the settings widget for that component, which is generated from the component’s properties. Any changes to those settings then call on the component property’s setter, which handles what happens when a value is changed.

Since these changes, writing tools for the components has been a breeze. It’s amazing what a difference a good design can have on development efficiency. I’ll go over the Rig Builder interface and its various tools next time.